Author Interview

What is The Doctor and the Diva about?

The story begins in 1903, in Boston. A young, Harvard-educated obstetrician who is a rising star in his profession becomes dangerously attracted to a patient – a lovely opera singer. She turns to the doctor for help in conceiving a child. The doctor becomes so drawn to her that he takes a great moral risk – a secret he can share with no one.

The novel is based on ancestors, and hundreds of pages of family letters. Who were those ancestors?

The married couple in the novel, Erika von Kessler and her husband Peter, were inspired by my son’s paternal ancestors – his great-great grandparents. They lived in Boston at the beginning of the twentieth century, and they were an extraordinary pair. Even by modern standards, they dared to live in bold, highly adventurous ways.

What moved you to write about them?

I can remember the moment I first heard about the great-great grandmother, the woman whom I call “Erika” in the novel. I was nineteen years old, living in Santa Barbara. A friend had gone away for the weekend, and she’d loaned me her beachfront apartment. It was around midnight, and I was lying there in the arms of a young man I barely knew. He later became my husband, but at that moment we were just beginning to know one another. He talked about his grandfather, who had recently died. Suddenly he said, “When my grandfather was a little boy, his mother deserted him and her husband and moved to Italy to develop her career as an opera singer.”

The idea of a privileged woman in early twentieth century Boston who abandoned her husband and small child for the sake of her art … the thought of it amazed me. Then I couldn’t decide: did I admire her and want to applaud her courage? Or was it heartbreaking that she’d deserted her little boy? The tension of all those conflicting feelings drew my imagination to her.

How did you manage to learn more about her life?

Early in our marriage, my husband and I moved to Boston. Every day on my way to work, I walked through the Back Bay neighborhood where these ancestors had once lived. Erika’s childhood home stood on Commonwealth Avenue. Her father was a famous physician, and they lived in a rather grand house with two archways.

When I went up to the front entrance and cupped my hands against the glass pane to peer inside, I saw that much remained the same as it had been in the late nineteenth century. The wide staircase was still paneled in black walnut, and I imagined her fiancé Peter mounting the steps, and her voice echoing down to him while she sang from the parlor upstairs.

Why did their story seem so haunting to you?

When I stood across the street from “Erika’s” house, I could almost see a young girl’s face -- her face -- staring back at me from an oval window on the third story. I had a strange sense of god-like omniscience, because I knew things about her life that she couldn’t foresee -- how her husband would one day be forced to divorce her and take custody of their small son; how she would sing in I Puritani from Montepulciano, Italy; how her little boy would write her letters that were never delivered to her.

What about her husband? How was he unusual?

What about her husband? How was he unusual?

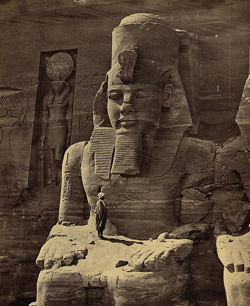

Her husband was a fascinating person as well. He was British, a highly successful international businessman – an importer of Egyptian cotton, among other things. “Peter” was a man of voracious curiosity, a naturalist, a lover of flora and fauna. He imported the first chimpanzees to the London Zoo, where he later became a Director. He traveled across four continents, and ventured into remote places, keen on seeing and experiencing everything. And he wrote prolific, richly detailed letters.

He was the sort of man who’d ride a camel through the Egyptian desert to visit a tribe of Bishareen nomads, where he’d move from tent to tent, tasting their dried bread and goat’s milk.

Or he’d head to a friend’s lush Caribbean coconut plantation, where they’d ride at midnight in a buggy along a beach, with vampire bats flying overhead... He’d slash a path through a rainforest with his machete, or he’d travel upriver in South America toward a waterfall that few Europeans had ever seen.

A third character in the novel – the fertility doctor Erika and Peter consult – becomes a crucial figure in their lives. Many readers may be surprised to learn that fertility specialists existed in 1903. Were their treatments effective?

Certain procedures that many people might regard as “modern” – such as artificial insemination – were actually being practiced more than a century ago, but doctors had to conduct such work surreptitiously. They risked grave moral condemnation.

The Doctor and the Diva takes place at a real turning point in medical history. Prior to that era, if a couple were unable to have children, the fault was always placed on the woman. The problem was always thought to be due to a “barren” wife. In the latter half of the 19th century, physicians began to discover a startling truth: a man could be virile – he could be sexually potent – and yet he might also be infertile.

What led to that discovery?

As far back as 1677, a man in Holland named Leeuwenhoek looked through a microscope and saw sperm. By the mid-nineteenth century, physicians had begun to study human sperm with real scientific scrutiny. An American physician named Dr. Sims became known as “the father of modern gynecology.” Dr. Sims would follow married couples into their homes. He’d wait behind a bedroom wall while a couple had intercourse, and then he’d rush in and probe and take measure of things under the microscope. He invented an instrument known as the “impregnating syringe.”

During the Victorian era, how was he allowed to do that kind of research?

Dr. Sims shocked and appalled many people. But the majority of patients who filled gynecologists’ consulting rooms during the nineteenth century came there because of infertility. Some were so desperate to conceive a child that they were motivated and willing to cooperate.

There’s some statistical evidence that infertility was more prevalent during the 19th century than it is today. One cause was gonorrhea, which was epidemic and incurable then. During the 1870’s, there was one rather sad and touching case that convinced a professor of obstetrics at the University of Pennsylvania that husbands -- as well as wives -- were part of the equation. A female patient came to him, begging for an operation to help her conceive. While the doctor was trying to decide if he ought to perform the procedure, the woman’s husband presented himself, feeling very guilty about all his wife’s anguish and distress. He told the doctor that he believed his gonorrhea – from which he’d been suffering for many years – must be the root cause. So, after an examination of the husband’s semen under the microscope, it became evident that the man was sterile. This proved a revelation for the professor of obstetrics. Afterward, he told his colleagues: I beg of you, be sure to examine the husband, as well as the wife.

A century ago when doctors performed artificial insemination, did they use a husband’s sperm, or a donor’s?

At first, during the mid-nineteenth century, they relied on the husband’s sperm. But by the 1880’s and 1890’s, certain gynecologists did begin to use donor sperm – although they rarely revealed what they’d done until decades later.

Older women in the family shared their memories with you, and rumors they’d overheard. What else did they say about the real Erika?

One elderly cousin, born in England in 1898, came to visit the U.S. As a child, she’d heard a lot of whispering about her American aunt. She’d heard that “Erika” had a baby daughter fathered by a man who was not her husband…. She’d heard that long after Erika had deserted her son, she’d appeared one day, unannounced, at her son’s boarding school.

The novel draws upon hundreds of pages of family letters. Where did you find those letters?

The novel draws upon hundreds of pages of family letters. Where did you find those letters?

After my husband and I had lived in Boston for nine years, we decided to move back to the West Coast. We drove cross-country and stopped at his aunt’s ranch in the Sierra Nevada foothills. Like me, she had a passion for genealogy. From the moment you stepped into her house, you felt the presence of the ancestors…. Huge family portraits stared down at you from her living room walls. She had a little gallery of framed butterflies -- a dozen exquisite butterflies that her grandfather “Peter” had meticulously painted with hair-thin brushes.

Where are the letters I’ve heard so much about? I asked her. The aunt brought out hundreds of pages of correspondence. Reading them just amazed me. I realized that these ancestors had led far bigger lives than I’d imagined. Their voices could be heard in those pages. There was so much detail and adventure – nights spent exploring winding streets in Tangier, or visits to a coconut plantation in the Caribbean where the guests told ghost stories after dinner...

If Erika were alive today, do you think her career vs. motherhood conflicts would be any different?

If Erika were alive today, do you think her career vs. motherhood conflicts would be any different?

Her guilt and anguish would probably be very similar to that described in the novel. But I think that today, the courts and society would have allowed her more flexibility with respect to staying in contact with her child. In those times, transatlantic airplane travel wasn’t an option. She couldn’t fly back and forth to visit her son for a few days. In that era, if a mother moved across an ocean and settled in another country, that was it -- she was gone. And from a legal standpoint, she surrendered her rights to custody.

It’s interesting to think about her husband “Peter” and his mode of parenting. In real life, “Peter” was often an ocean and a continent away from his young son, and he did a lot of his parenting by letter. At the age of seven, the boy was placed in boarding school, and during vacations, his father arranged for him to live with a family like the “Talcotts” (as described in the novel). The boy was basically “mothered” by a colleague’s wife. But despite his father’s long absences, the real-life Quentin always regarded his father as a towering, loving figure – and as an extraordinary man.

And long after Erika’s death in 1918, her son remembered his mother with a certain pride and respect. His daughters told me that as they were growing up, “Quentin” always kept a framed photograph of his mother on top the Steinway piano – a picture of Erika dressed in her operatic regalia.

What did you enjoy most about writing The Doctor and the Diva?

Apart from the joy of composing the fictionalized story, I loved doing the research. It was deeply pleasurable to steep myself in another era, and revel in all those exotic lands described in century-old family letters.

Learning about the history of medicine and the working life of a 1903 obstetrician like Dr. Ravell – that was also fascinating. And the music! I cannot tell you how it nourished my soul and my senses, to listen to the gorgeous arias that Erika sang. Had it not been for my son’s ancestor, I might have missed out on a whole domain of thrilling and lovely music.

How long did it take you to write The Doctor and the Diva?

About six years. I wrote a first draft of the novel in the mid-1980s, but the result was lifeless and stale. I packed up those pages and stored them in a box for twenty years.

Then, after a couple of decades passed, I envisioned an entirely new way to frame the novel. This time I would begin Erika’s story not through her own perspective, but instead through the eyes of the young doctor who was becoming obsessed with her, a man who would take a terrible risk and jeopardize his career because of her.

How did you research the novel, and balance factual information with storytelling?

First, I read the family letters with great scrutiny, always on the lookout for material that might be transformed into a scene. I imagined the exotic locales as stage sets where dramas might unfold.

Like any good student, I brought home musty books and old recordings from University and public libraries, and while I pulled out my pen and took careful notes, my conscious and unconscious mind were both at work. I was constantly on the hunt for just the right, historically apt detail. For example, when Erika is confined to her bed during childbirth, Doctor Ravell puts a ball of cotton soaked in chloroform into a tumbler, and he tells Erika to place the glass over her nose. After she breathes its vapors, the tumbler slides from her hand and rolls along the carpeted floor. That’s all you need to evoke pain relief during childbirth in 1904 – one detail like that, just a whiff.

What was the creative process like?

What was the creative process like?

I researched for a couple of years before the formal, serious writing of the novel began. While I was gathering the historical facts, an entire scene would often come to me. Whenever I “overheard” conversations between the characters, and I’d grab scrap paper and capture their dialogue quickly. I jotted down whatever the characters were saying, even when I had no idea where in the novel that exchange might occur. I tossed the wildly scribbled scenes into a box and saved them. As I researched, the dramatic scenes accumulated, and the story line began to take shape. (Later I found that the dialogue I’d “overheard” barely needed revision. It came out clean, and sounded natural.)

For many months I refrained from doing any “real” writing. Instead, I kept listening to ravishing arias and consuming a feast of fascinating information – about the history of medicine and opera, about the training of vocal artists, or about apartment hunting in Florence a century ago.

When I finally sat down to begin the newly envisioned novel in earnest, I pulled out that box of spontaneously scribbled, random scenes and saw very quickly how they ought to be sequenced. Even before I began to compose the first page, my unconscious had already done much of the work. A new draft erupted from me with great speed and excitement.

On a deeper, thematic level, what is THE DOCTOR AND THE DIVA about?

The themes are too many to count, but I will say this. Several characters in the novel commit unthinkable acts. I’ve always been interested in the challenge of seeing a character’s situation with empathy, so that even the most shocking choice or appalling actions might become understandable.