"Father of Modern Gynecology"

Even in past centuries, certain bold doctors experimented with fertility treatments now regarded as modern. They undertook such work behind veils of secrecy and at the risk of moral disapproval. An illuminating moment in the scientific understanding of human reproduction occurred when sperm was first viewed through a microscope invented by a Dutchman, van Leeuwenhoek, in the late 17th century. This opened a window through which early pioneers in gynecology began to see endless potential and possibilities.

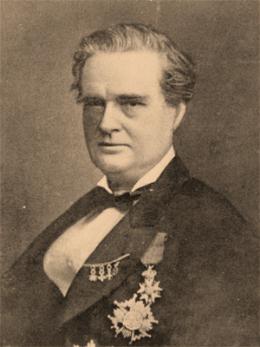

Artificial insemination, which can be achieved by relatively simple technology, has long been practiced. In 1785, the revered Scottish surgeon John Hunter recorded a case in which he successfully inseminated a female patient with her husband’s sperm, and the birth of a living infant resulted. In 1866, the brilliant American physician John Marion Sims – referred to as “the father of modern gynecology” -- reported a similar triumph.

By the mid-19th century, it had become clear to Dr. Sims that infertility – which had historically been blamed solely on a “barren” wife – might also arise from a husband’s reproductive difficulties. Based on his clinical investigations, Dr. Sims proclaimed the radical notion that a sexually potent man could be sterile. He performed 55 artificial inseminations for six couples. Sims and other innovative gynecologists of the 19th century invented variations of the “impregnating syringe,” as well as other tools and implements so that sperm could be strategically stored, manipulated, and optimally positioned for the purpose of facilitating conception.

In his many clinical attempts to assist conception, Dr. Sims used only a woman’s husband’s sperm – and that stirred moral controversy enough. But in 1884, the first successful insemination with donor sperm reportedly took place. A Quaker couple consulted Dr. William Pancoast, a professor at the Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, to help them conceive. When the husband’s semen was examined, he was found to be “azoospermic” (i.e., sterile). Dr. Pancoast allegedly turned to his circle of six medical students, and they agreed that one of them should serve as a sperm donor. Under the guise of performing some other treatment on the wife, the doctor then chloroformed the woman and artificially inseminated her with the sperm of the medical student deemed to be “the best looking.” A baby boy was born to the woman nine months later. The mother was never told what had happened, although the doctor supposedly informed her husband. Only in 1909, after Dr. Pancoast’s death, did one of the medical students who had been present reveal the story.

By the 1890’s, other medical experts performed treatments with donor sperm. Such procedures had to be undertaken on such a clandestine basis that one physician, Dr. Robert L. Dickinson, did not publish reports of what he had done until another forty years had passed.

Apart from the fear of moral condemnation, early fertility specialists may have preferred to keep the exact nature of their procedures veiled for another reason: their statistical rate of success was undoubtedly low. Many doctors found the treatment of infertility the least rewarding aspect of their practice. Their clinical trials and experimental work were hampered by a couple of key issues. First, many male patients were sensitive to any questioning of their “virility;” and found the act of submitting to a semen analysis repellant, so physicians did not require them to do so. Secondly, the timing for ovulation was poorly understood during the 19th century. In the 1870’s and 1880’s, a woman was thought to be most fertile during the time of menstruation. (This notion was soon questioned as medical experts noticed that breastfeeding mothers, in the absence of their periods, sometimes became pregnant.) It was not until well into the twentieth century that medical investigators determined that ovulation occurred at mid-cycle.

The possibility of freezing sperm has long inspired the medical imagination. In 1866, the Italian physician Dr. Paolo Mantegazza suggested that before soldiers went off to battle, they should leave behind frozen sperm, so that in the event of their deaths, their widows might bear them posthumous children. Effective methods for cryopreservation (freezing sperm) were not perfected, however, until the 1950’s.